We have finally reached the sixteenth president. When, at the beginning of the week, I take the Mike Venezia biography on Lincoln off the bookshelf, Simon says: “I read that already, Mom--don't you know?”

We have finally reached the sixteenth president. When, at the beginning of the week, I take the Mike Venezia biography on Lincoln off the bookshelf, Simon says: “I read that already, Mom--don't you know?”“On your own?”

“On my own.”

“Wonderful!” And then, because sometimes I have little control over my mouth, I say: “Why?” Simon reading a whole book on his own, cover to cover—that's new.

“Because it's Lincoln, Mom!” Simon says, impatiently.

“Can you read it to me again?”

“Sure.”

It's December in Miami. The windows are wide open. The air is crisp and cool. We lie on the day-bed in the Learning Room. Simon reads. I smell the grass, the trees; I hear birds. The mail-man comes up the walkway and we take a break to check if we got another holiday card. We make hot chocolate and take our mugs back to the Learning Room.

“I have to finish Lincoln all today, Mom. We cannot do Latin or German. After Lincoln, I have to read about Andrew Johnson right away. I have to find out what happened after Lincoln was shot.”

“OK. Why is Lincoln so super interesting to you, Simon?”

“Because he ended slavery. Even though he was very ugly, he was great. The presidents before him all sucked.”

“Sucked” is the new word d'jour. George and I choose our battles when it comes to colorful language. Simon can say “sucked,” but he cannot write it. We've defined formal and informal speech.

Simon finishes Lincoln, and then this child who does not read with pleasure immediately takes Johnson off the shelf and starts reading.

The Venezia biographies all begin with a general assessment. Venezia writes about Johnson that he “wasn't as skilled a leader as Lincoln had been...he was stubborn and racially prejudiced ...very little was accomplished.”

“I don't want to read anymore. Johnson sucked, too, Mom. I'll just look at the pictures. I'll read more tomorrow.”

It's a beautiful day in Miami, I think, looking out onto a Hong Kong Orchid and a Meyer's Lemon drooping with fruit. Simon lies next to me, flipping through the book.

“Look at this,” Simon says. He points to a picture of Richmond, Virginia, all rubble, all bombed out. “Why do people do that?” he asks.

Instead of saying “Why do you think?” and letting him figure it out, I proceed to do an information dump. I've been tired this week, somewhat self-absorbed. I talk of military strategy, of controlling territory, of destroying not only the enemy's cities and forts, but also his spirit.

“Did kids die in Richmond?” Simon asks.

“Some kids died, I'm sure.”

“Moms?”

“Moms, too.”

Simon is quiet. Then he says: “People are mean.” He continues looking through the Johnson biography.

I can hear the neighborhood kids congregating down the street. They are on vacation. They have a basketball. I hear it bouncing off the pavement. Soon they will come and ring the doorbell, asking for Simon.

“Mom, look at this picture,” Simon says. “Look how many people were in the room when Lincoln died.”

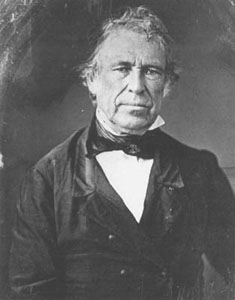

He's gazing at the Alonzo Chappel painting--see above. I tell Simon that I know from my readings on Lincoln that the scene is fictional. Lincoln died at a roadside inn with only a few people in attendance, not a mob of all the important political figures of the time.

“Maybe the painter wanted to show how many people would miss him,” Simon says.

“Maybe,” I say, nodding.

The doorbell rings and Simon bolts off the bed and runs out of the room. He ducks his head back in. “Can I go play?”

“Go play.”

Many people would miss him, Simon had said. I miss him.

It's been a week of too much feeling. Layered on top of the exhausting, excessive, and inescapable joyousness of the season, have been my readings about Lincoln. He never went to school; he taught himself everything, even the law. He lost two of his four sons during his life-time, all much loved. He had so many friends, they made up towns, cities, states. He cared little about all the stuff that doesn't matter: clothes, manners, appearances. Acutely aware of weight of his responsibilities, the full impact of his actions, and the full measure of his--and everyone else's losses--he struggled with melancholia.

I've poured over his key speeches. I'd never read them closely. There is something intimate, exposed, unabashedly personal about his voice, as if he's speaking to you with no reservations from the center of his heart's obsessions.

You probably remember Gettysburg and the 2nd Inaugural, but here is his Farewell Address, delivered as he was leaving Springfield, Illinois, to begin his first term. War was looming.

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you, and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.

Lincoln has been on my mind this week. I lack his faith that “all will yet be well.” This week the Copenhagen meeting came to an end, and the Health Reform Bill went up for a vote in the Senate. How will we bring about all the radical changes we have to make for the sake of our planet, our economy, our children and grandchildren? Following the wranglings about health reform these last months, I've felt stuck in a Dickens novel—with few exceptions, each character more vain, foppish, thoughtless, reckless, and undignified than the next. I realize that the gains made by the Health Reform Bill are huge, but they seem so much less than what is necessary, a bill brokered in an age of relentless compromise, indomitable special interests, and men, mostly men, who are not Lincoln. And there are so many bills to go.

Dark thoughts in sunny Miami this holiday season.

Some last words by Walt Whitman:

This Dust Was Once the Man

This dust was once the man,

Gentle, plain, just and resolute, under whose cautious hand,

Against the foulest crime in history known in any land or age,

Was saved the Union of these States.

Dark thoughts in sunny Miami this holiday season.

Some last words by Walt Whitman:

This Dust Was Once the Man

This dust was once the man,

Gentle, plain, just and resolute, under whose cautious hand,

Against the foulest crime in history known in any land or age,

Was saved the Union of these States.

the walls? Did anyone give them a blanket?

the walls? Did anyone give them a blanket?

asn't raised with Thanksgiving, and the menu is too full of things sweet and mashed for my taste. Moreover, we have no extended family to speak of that we could share it with. Most of my family is abroad, George's parents are dead, and his older kids have tended to spend it with their mom. Now that they are all grown-up, they often visit the families of their significant others, American families that have strong Thanksgiving traditions.

asn't raised with Thanksgiving, and the menu is too full of things sweet and mashed for my taste. Moreover, we have no extended family to speak of that we could share it with. Most of my family is abroad, George's parents are dead, and his older kids have tended to spend it with their mom. Now that they are all grown-up, they often visit the families of their significant others, American families that have strong Thanksgiving traditions.

Steadily, Simon continues to read a presidential biography every week: Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce. Simon notices, about each one, that he, too, could not fix the problem of slavery.

Steadily, Simon continues to read a presidential biography every week: Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce. Simon notices, about each one, that he, too, could not fix the problem of slavery.